Social science of the internet intrigues Stanford senior Qitong Cao, 2018 Rhodes Scholar

Qitong “Tom” Cao, a senior majoring in political science, is an honors student in the Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law. He is simultaneously earning a master’s degree in management science and engineering, with an emphasis on computational social science. He will represent his native country, China, as a 2018 Rhodes Scholar.

It didn’t take long for Qitong Cao (pronounced cheeTUNG tsao), an international student from Nanjing, China, to find his intellectual passion at Stanford.

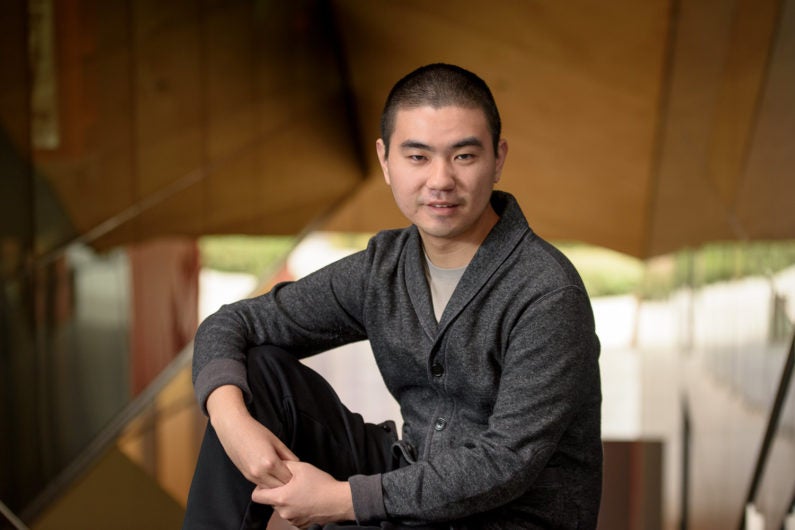

Stanford senior Qitong Cao will represent his native country, China, as a 2018 Rhodes Scholar at Oxford University. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

During his first year on the Farm, Cao heard that a renowned political scientist would be giving a guest lecture, “Reverse-Engineering Censorship in China.” After finishing classes for the day, Cao walked to the Huang Engineering Center, eager to hear Gary King, director of the Harvard Institute for Quantitative Social Science, talk about his research.

“I have always considered myself a huge beneficiary of the internet, because it allowed me to gain access to a tremendous amount of knowledge, including how to apply to Stanford,” Cao said. “I developed a keen interest in the sociopolitical impacts of the internet and social media.”

In the 2014 lecture, King talked about the methods he and his colleagues, including Jennifer Pan, now an assistant professor of communication at Stanford, employed to study social media censorship in China. They found that posts that criticized the Chinese state, its leaders and their policies were routinely published, but posts with collective action potential were much more likely to be censored – regardless of whether they were for or against the state.

“Their Science paper, which I read very closely after the talk, really got me interested in political science,” Cao said. “I was really intrigued by how big data could be used to reveal sociopolitical phenomena.”

Forging an academic path on the Farm

It was the beginning of an exciting intellectual journey for Cao, who is now a Stanford senior majoring in political science and an honors student in the Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law. Cao is simultaneously earning a master’s degree in management science and engineering, with an emphasis on computational social science – a field that uses computers to model, simulate and analyze social phenomena.

“I deeply appreciate the breadth of my Stanford education, especially the opportunity to pursue a liberal arts bachelor’s degree and a technical master’s program at the same time,” Cao said. “That has allowed me to think about an issue from multiple standpoints and to understand how different methods may complement and reinforce one another in coping with real-world problems.”

Cao said he was grateful to the mentors who have guided him on his academic journey, including three senior fellows at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies – Francis Fukuyama, Larry Diamond and Jean C. Oi, who is also the William Haas Professor in Chinese Politics in the Department of Political Science.

Studying the internet’s sociopolitical impact

In this, his last quarter at Stanford, Cao is putting the finishing touches on his honors thesis, “The China Wide Web,” a topic that reflects his abiding interest in the sociopolitical impacts of the internet and social media.

“When there is no universal election to gauge public political inclination, a regime will have to face what I call the ‘information dilemma,’” Cao said. “It needs accurate political information from its citizens to understand their political attitudes and adjust policies accordingly. But simultaneously, it has to prevent citizens from exposing such information to each other, which could lead to protests threatening its rule. The dilemma becomes more complicated in the era of the internet and social media, whose borderless nature impedes governmental efforts to collect citizens’ information from foreign content platforms, or to insulate citizens from exposure to unfavorable information.”

I started to get the feel of the English language reading “Harry Potter,” which was very helpful, because I was reading other materials in English, such as Wikipedia. Learning English opened a new window for me.

Qitong Cao

2018 Rhodes Scholar

In his thesis, Cao argues that the Chinese government has come up with a new way to resolve the information dilemma by constructing a domestic cyberspace, in which internet platforms restrict the spread of political information among their users but provide user data to the government.

“This way, the government can get an overview of the political orientation of its population while preventing circulation of signals that could generate social instability,” he said.

“But issues related to social media are not only a problem in China,” Cao said, noting that several prominent internet companies in the United States also possess significant portions of user data from their online activities. “These data can be used to train algorithms to make predictions about certain user groups, which could give rise to huge sociopolitical effects.”

Cao looks forward to delving deeper into those issues at the University of Oxford, where he will begin his graduate studies as a 2018 Rhodes Scholar – representing China – in the Oxford Internet Institute, a multidisciplinary research and teaching department dedicated to the social science of the internet.

Cao is the first Rhodes Scholar from China whose degree is not from a Chinese university. When he graduates in June, his parents will be in the audience for Commencement – and their trip to the Farm will mark their first time abroad.

Learning English at Hogwarts

Like children around the world, Cao was entranced by the adventures of Harry Potter at the Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry and could hardly wait for each book in the J.K. Rowling series to be published. After reading the first five books in Chinese, he became impatient waiting for the sixth, Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince. So, he convinced his parents to buy the entire set in English, and sat down, dictionary at the ready, to read them from the beginning.

“As I proceeded through the novels I looked up words thousands of times, I would guess,” Cao said. “I didn’t know how to pronounce a lot of those words, so I came up with my own pronunciation. I started to get the feel of the English language reading Harry Potter, which was very helpful, because I was reading other materials in English, such as Wikipedia. Learning English opened a new window for me.”

At the Nanjing Foreign Language School, Cao continued studying English, though most of his classes were in Chinese. After receiving a scholarship to study abroad, he spent one semester as an exchange student at St. Louis University High School, a Jesuit college preparatory school for young men, and as a guest with two host families.

Cao said his American classmates were very interested in all aspects of China and his life there, and asked him and the other two exchange students from his high school lots of questions.

“In retrospect, I think it was a great way for people from different cultures and different countries to interact,” he said. “Telling them about my life was a great way to address some of their misunderstandings about China.”

During his first year at Stanford, Cao joined the Forum for American/Chinese Exchange at Stanford (FACES), which holds an annual two-part summit for 40 delegates that opens in October at Stanford and concludes in March at Peking University. Cao, who served as the organization’s co-president in 2016-17, led summit programming efforts for three years.

“I believe strongly in the importance of cross-cultural communication,” he said. “It is an extremely touching experience to see how our 40 delegates from China and the United States and elsewhere develop friendships and how their bonds deepen when they meet again a half year later,” he said. “Tremendous tension could arise between the two countries from a lack of mutual understanding. Given the importance of U.S.-China relations to the future of the world, person-to-person exchange between university students in the two countries are all the more crucial.”